When Jay Atherton and Cy Keener met in grad school at the University of California, Berkeley, they discovered in each other a rare constellation of common interests: minimalist architecture, rock climbing, and “not talking.” After graduation, Atherton moved back to his hometown of Phoenix, Arizona, and purchased a downtown lot. Wanting to build a house, he asked Keener—–a pro carpenter, then living in Colorado—–to help with design and construction. Six months later, “His house became our house,” says Keener. “It became obvious the only way it would get built was if I shared the mortgage.” Atherton cackles: “I suckered him down here.” The roommates are now business partners: They founded a design firm, Atherton Keener, in 2007. On a 110-degree day, they invited us in for a tour.

Keener: When we first came to Phoenix, we realized: People move here for the "weather," but you drive around and you see that everyone is either outside squinting or inside with their shades drawn tight. So we wanted to create a house that was still connected to the outside.

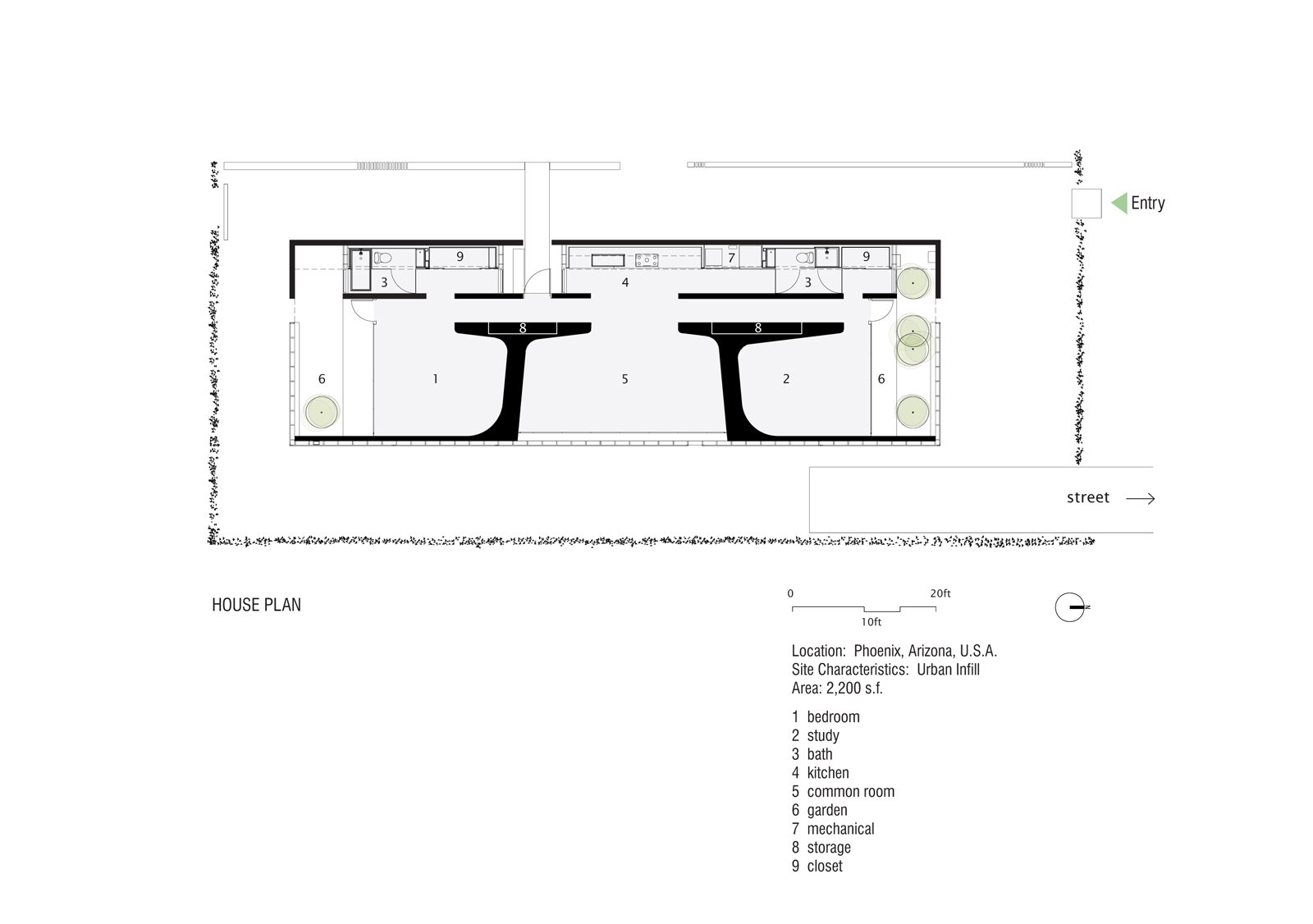

Atherton: The house consists of three rooms: a bedroom on either end of the house and a living room in the middle. Each room faces a different direction, and each receives light in a different way. The west gets extreme sun exposure in Arizona, so we don’t have any openings on that side, except for the front door. The kitchen, laundry, and two bathrooms run along that wall and they are very compact, like in a ship or an RV. The hallway is a clear long path that connects everything, with a wall of translucent glass on one side and black plywood cabinets on the other.

Keener: Because of practical and budgetary reasons, we didn’t have the luxury of using crazy materials. Concrete block has been a part of building in the desert for a long time. The screen that wraps three sides of the house is just a standard thing you see everywhere down here—–generally used to shade parking lots and kids’ playgrounds. The floor is concrete. The walls are drywall. Our interest was in using standard things on a relatively unremarkable site and creating something that was more than the sum of its parts.

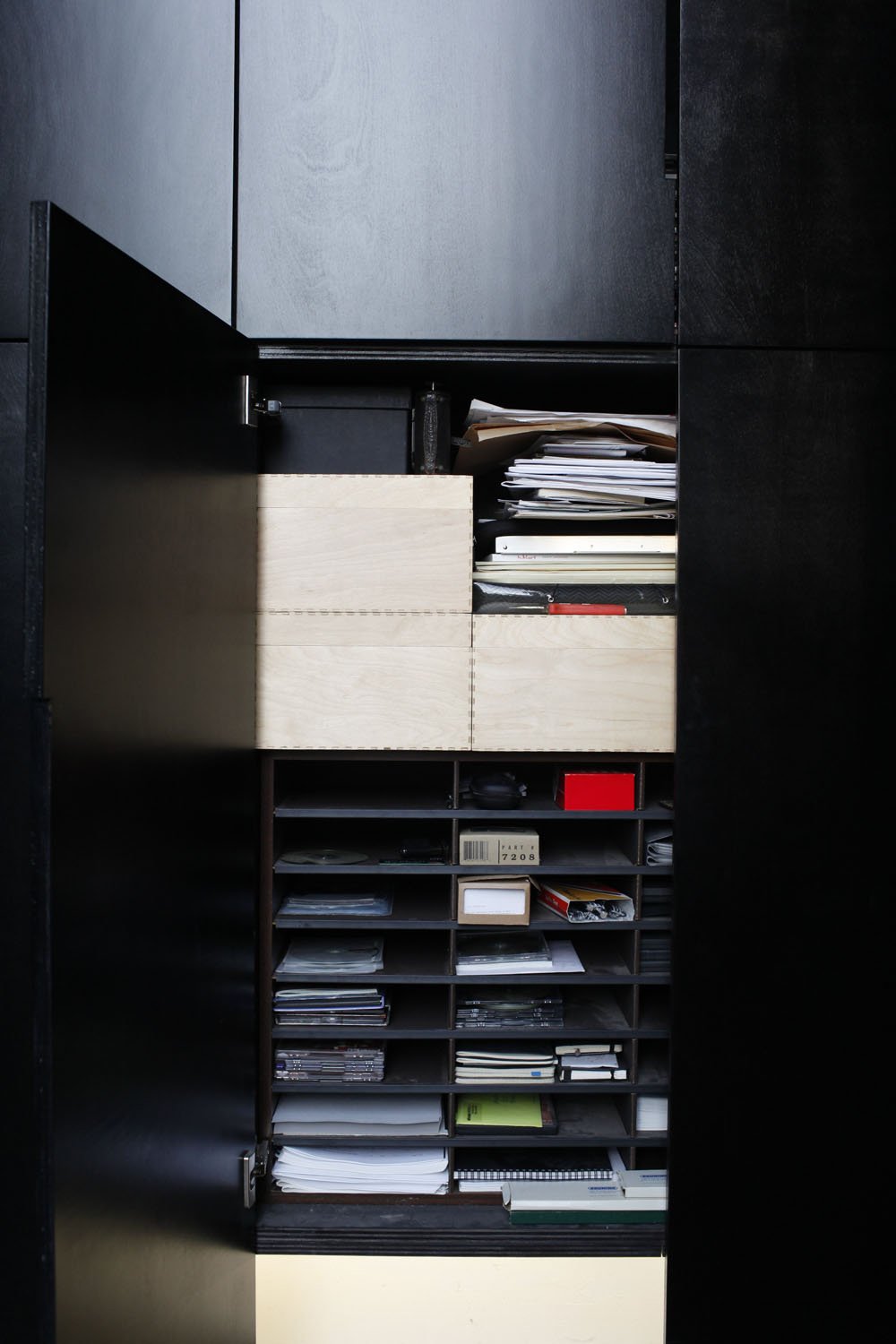

Atherton: The design process was fairly rigorous and very slow. We were the clients and the builders and the designers, so we were really our own worst enemies. Instead of just going to Home Depot and buying everything, we tried to make as many things as we could by hand, so that they would agree with the rest of the house. We wanted to accomplish as much as we could with just a few materials.

Keener: Basically the only things in the house that we purchased were the plumbing fixtures and the appliances. We made all the cabinets—–in the bathroom, kitchen, storage closets, and hallways—–ourselves, out of plywood that we dyed black. For a while the sinks and tubs were going to be concrete. But it never felt right. In the end we made them by hand, out of marine-grade plywood and marine epoxy resin.

Atherton: One of the challenges we faced was that at some point, the design started to reject ideas.

Keener: It was important that the rooms be pure spaces. The curved walls are just there to capture the light conditions from the windows. We’ve been very meticulous about locating distractions—–like closets or light switches—–in the hallway. We wanted to make something quiet enough to receive what’s going on outside. It helps that we don’t carry a lot of furniture with us. Before we moved into the house we lost our lease on a rental and shared a five-by-ten storage unit. It wasn’t even full; it was like half full. People come in and they say, "Whoa, art would look so good on these walls." But I’ve never felt like this house is missing anything.

Atherton: There are some uncon-ventional aspects to the house, but we’re also using it as an architecture studio, and a pavilion, and a warehouse. If we’re interested in something, we can bring it in and experiment with it. When we were working on an art installation, we had two 300-pound blocks of ice in a tub in the middle of the room. At one point there were 800 yards of fabric piled up. We have a dog, and when we had all that fabric lying around, he loved it, he was like "Oh my god, it’s furniture." And then it was gone.

Atherton: Our friends know that this house lacks a certain amount of comfort, but everyone adapts to what it does have. When people come over to eat, we usually sit on the floor—–we keep it really clean—–or outside. We’ve all adapted to what it means to not have a dining table. We don’t have a couch. It can be a bit of a problem. Like when we have our girlfriends over it’s hard to make them just sit on the floor or on a chair. And it’s very presumptuous to have the bed as the main piece of furniture in the house. One of the nice things about having a girlfriend is, she has a couch at home.

Keener: The house isn’t static. A photographer friend uses the place for fashion shoots. The other weekend we had 40 people in the living room listening to a classical guitar, bass, and flute trio. One night this woman played a solo piece on the violin in the dark, and the moonlight was bright enough to cast shadows on the screen from the oleander outside. It was so beautiful.

We have been fairly open with sharing the house with folks and that’s been really rewarding. It always surprises me with how grateful they are and how pleased they are with the experience that they have here. I think that people appreciate being in something so clear and consistent. They use words like "peaceful" and "Eastern" and "meditative" and "calm" to describe the space.

Atherton: There are lots of examples in history where an architect builds a home, and from that home, his ideas develop, and he becomes more fully realized as an architect. It doesn’t necessarily make the best or easiest home. But it does set a trajectory for future projects. We were both interested in building something that we could learn from.

粤公网安备 44030602004129号

粤公网安备 44030602004129号